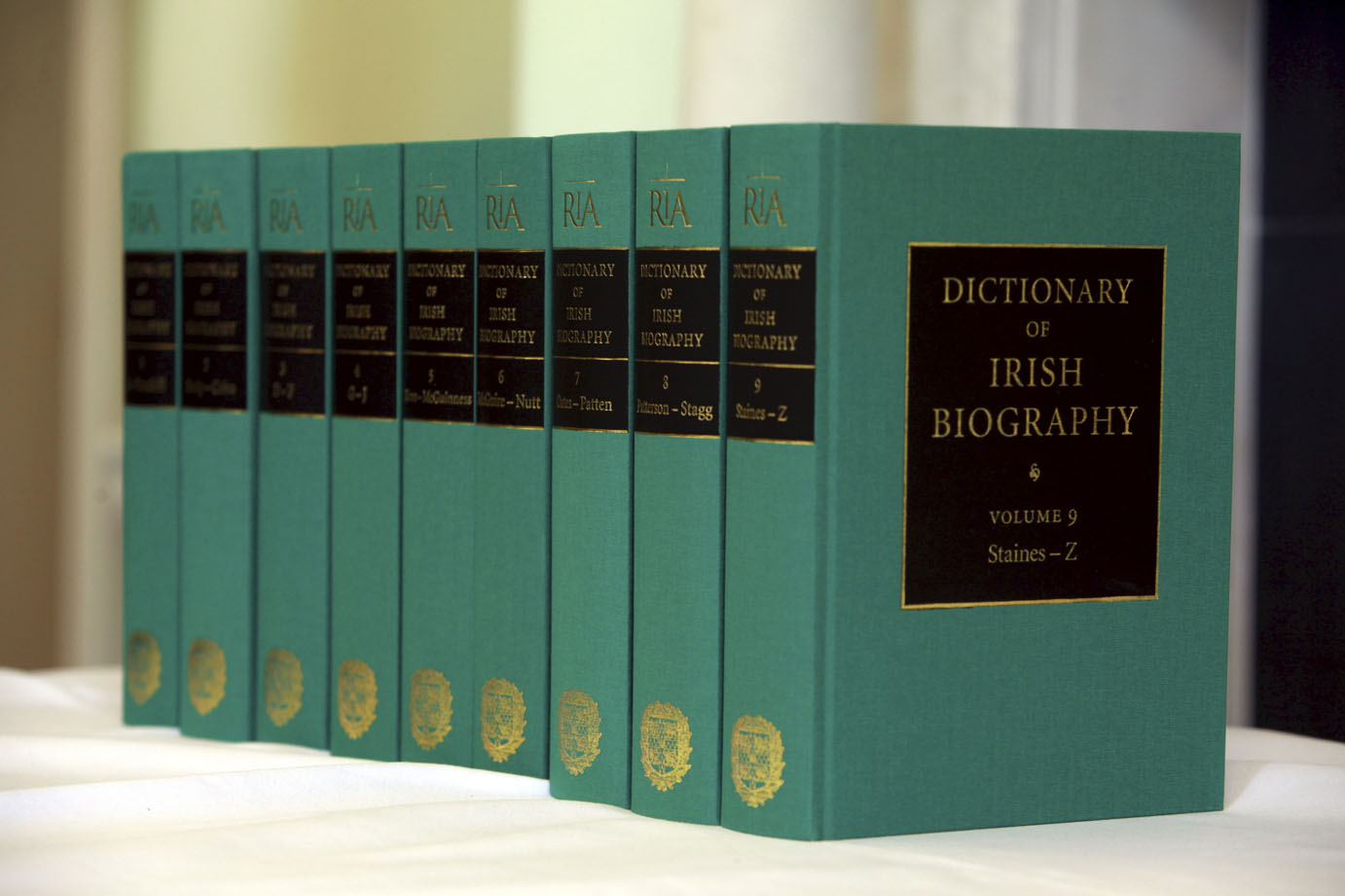

The Dictionary of Irish Biography (the DIB), published in nine volumes and online in 2009, is a work of truly historic significance. The model for all books of this kind, the old British Dictionary of National Biography (the DNB), appeared in instalments between 1885 and 1900 – and was not superseded until 2004, when the new Oxford DNB appeared. I expect that the DIB will likewise last for at least the next 100 years. Certainly, it will still be consulted long after we have forgotten most other works of Irish scholarship now in print – and its influence will extend to every field of Irish studies.

In a wider cultural perspective, the DIB represents a powerful statement of Irish identity – on a par with our language, our flag, our stamps and the harp on our euro coins. When the original DNB was published at the end of the 19th century, it included entries pertaining to Ireland. This was indicative of the mindset of the British establishment at that time. The Irish were part of the United Kingdom, albeit with their own distinctive tradition, like the Scots and the Welsh. There was no place for Irish separatism – not even for home rule, which was then the dominant Irish nationalist aspiration. The old DNB reflected that paradigm. It should be noted that we have not yet escaped from the yoke of the DNB. The new Oxford DNB published in 2004 continues to claim the Irish. The reason is, quite simply, that Ireland is regarded as part of Britain’s colonial heritage. While we cannot deny this aspect of our history, it is not the full story – and it is not an appropriate focus after over 90 years of independent statehood. We need to define ourselves in our own terms, not those of others. It is important, therefore, that we should have our own national dictionary of biography – and now, at last, we have it.

Máire O'Neill (Molly Allgood), Actor.

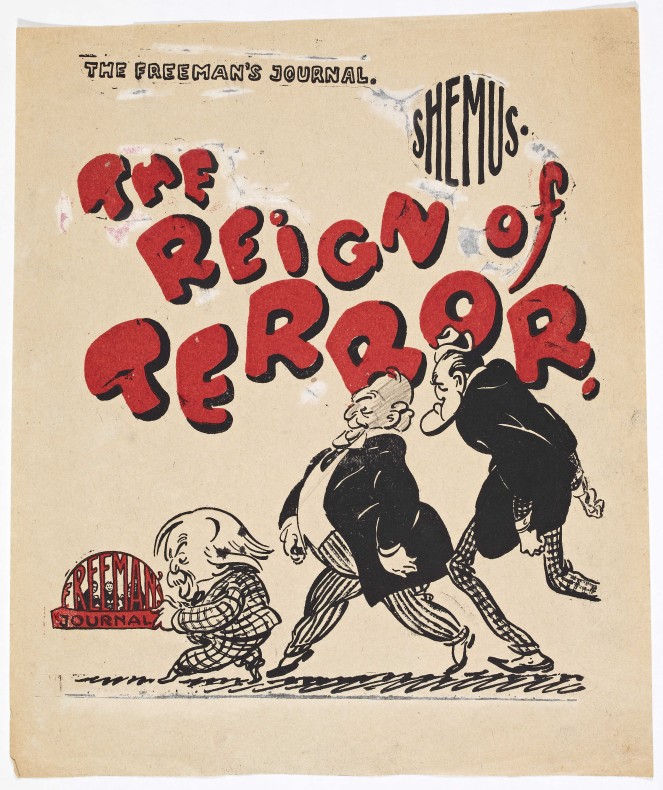

The original publication contained 9,014 signed biographical articles, and to be the subject of one of those articles one had to have made a mark in some field of human endeavour, to have died before the end of 2002 and to have been born in Ireland or had a significant part of one’s career in Ireland. The DIB is, however, a continuing project, and is regularly updated and extended online. A further 351 articles have been added since 2009, about three-quarters of which refer to persons who died between 2003 and 2007. The other additional articles are about persons who, though eligible for inclusion in the original publication, were inadvertently omitted. Two of the omissions thus rectified are Patrick Henchy, director of the National Library of Ireland from 1967 to 1976, and Ernest Forbes, the cartoonist ‘Shemus’ in the Freeman’s Journal, many of whose drawings for the Freeman are held by the National Library. Another is Rosie Hackett, whose name will be immortalised in the new bridge over the Liffey. Among those who died after 2002 and are now included are Charles Haughey and John McGahern. Unfortunately, there are no plans at present to issue the additional articles in book form.

A toast to Charles J. Haughey after topping the poll (1973)

Being included in the DIB – in print or online – is the ultimate proof that someone made it in Ireland. A similar distinction attaches to the many people who wrote the biographical articles, both those employed on the project and the various experts who, without monetary reward, were external contributors. The authors comprise a ‘who’s who’ of Irish scholarship today, and it occurs to me that part of the fun in editing the DIB must have been matching authors and subjects. Quite apart from the influence which the DIB will have as a work of reference, its influence will also be felt through the vital role it played in the professional formation of a generation of Irish historians. Many young historians, after post-graduate work, began their academic careers with a period of temporary employment on the DIB when the original publication was in preparation. Working on the DIB was a rite of passage for them. The high standards of research and writing which the DIB exemplifies will, accordingly, define Irish historical scholarship for many years to come.

This is greatly to be welcomed. For too long, the study of Irish history has been compromised by political and cultural agendas which have nothing to do with understanding the past. The long-running arguments about Irish history between so-called revisionists, anti-revisionists and post-revisionists are frankly tedious, and the time has come to move on from them. We can surely all agree that the study of history is about doing our best, in good faith, to discover the truth about the past – however inspiring, uncomfortable or mundane. Do the research, and let the chips fall where they will. The past happened, and cannot be undone; it made us what we are, for good and ill; and we have a duty to rediscover it and understand it, and to do so without illusions.

There is, therefore, no place for hagiography in history, not even perhaps when someone has earned the formal title of saint – and few deserve the opposite, outright demonization. Figures in the past were human, just like us – flesh and blood, each a mixture of good and the not-so-good, each with talents and shortcomings, each with failures as well as achievements. We do nobody any favours by enlarging them beyond what they were in life, by turning them retrospectively into plaster saints. Our heroes are actually more attractive, and their lives have more meaning for us, when we pay them the compliment of seeing them as real human beings, in all their complexity. In Brian Friel’s play Making History, Hugh O’Neill implores his biographer, Archbishop Lombard, not to ‘embalm me in pieties’, but to ‘record the whole life’ – and that is an admirable injunction to all historians.

Nowhere does the DIB fall into the trap of facile piety. It may be a statement of Irish identity, but it is a mature statement – not written in any spirit of national self-congratulation or with commemorative intent. It is instead grounded in a determination to find the truth, or at least ‘the best obtainable version of the truth’ (to quote Woodward and Bernstein, the Watergate journalists). Its aim is to record whole lives within the necessarily limited space allowed for each article. It seeks to understand and explain, not to judge. It is not God as He is sometimes depicted in images of The Last Day – with the virtuous on His right, the damned on His left. It is, in short, a work of scholarship. It provides a vital point of reference for anyone, anywhere in the world, who is interested in Ireland’s past – in the experience of the Irish people, both individually and collectively. It is a credit to its editors, James McGuire and James Quinn – and to the Royal Irish Academy, who sponsored it, and to the publishers, Cambridge University Press.

'The Reign of Terror' by Shemus (Ernest Forbes).

*Felix M. Larkin is vice-chair of the NLI Society and a member of the NLI’s statutory Readers Advisory Committee. He was an external contributor to the Dictionary of Irish Biography.