By Gabrielle Vergnoux, Conservation Intern, National Library of Ireland

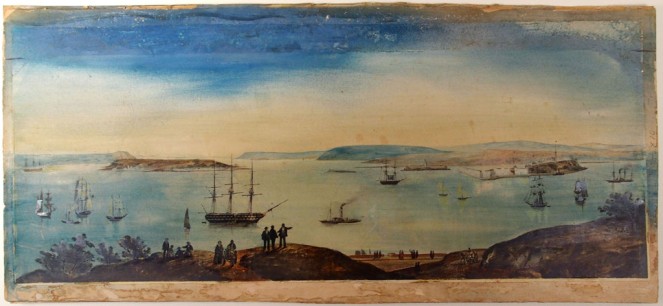

At first sight, an image of “Cork Harbour by Robert Lowe Stopford in 1862”, as is written on the verso, seems to do exactly what it says on the tin. The large marine landscape (29 x 71 cm), from the library's Prints & Drawings Collection, depicts figures bustling in the foreground, with an expansive vista of ships fading into the distance. Robert Lowe Stopford (1813-1898) was a popular Irish watercolour artist who represented landscapes and marine subjects, so we assumed the image was a watercolour.

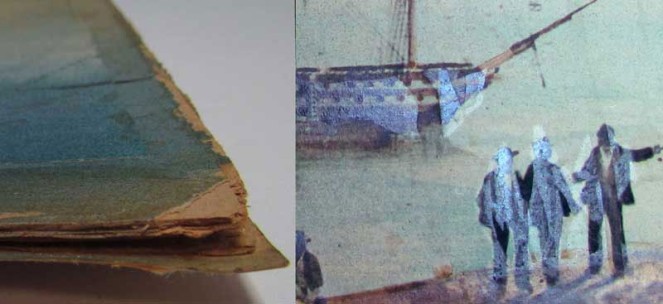

The picture, in rich sepia and bistre brown tones below a vibrant blue sky on a thick coated paper, was in fair condition. There was water-damage and dirt across the image on a thick delaminating board. The blue sky colour, which extends onto the board, had also faded from exposure to light.

After observation, we noticed some odd details. The painterly figures in the foreground were almost ghostly apparitions with fuzzy edges. There were uneven traces of a shiny substance, possible a gum or resin varnish, applied with a brush. The atypical colour balance of very bright blue and the musty browns were even more confusing. We could not see the back of the image, which can often tell more than the front, so before any treatment, we decided that a more in-depth examination linked with research was necessary.

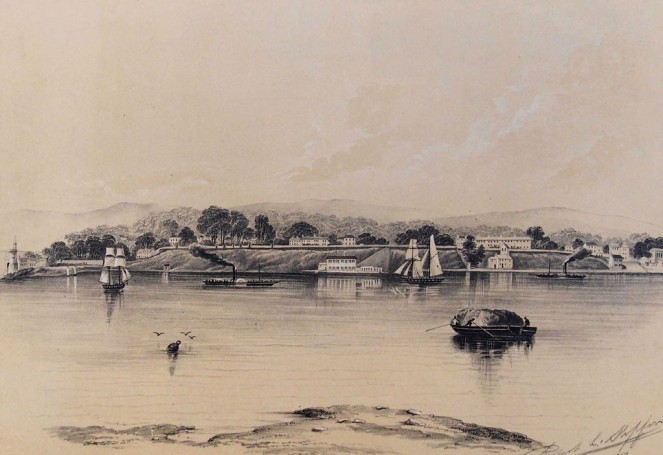

So was it a watercolour painting? Was the date written on the verso correct? Did Stopford, the watercolour artist, create it? Could it even be some sort of reproduction under watercolour over-paint? If so, which printing process could it be? This question is at the heart of our investigation. Let us try to better understand what secrets this curious image might reveal … A lithographic impression is made from a drawing made with thick wax on a stone, based on the principle that the water and the oil do not mix. As one of many economical methods of reproducing artworks from the 19th century, Stopford’s images were reproduced by lithography. So, could our image be a lithograph reproduction? We looked in the NLI Topographical print collection and found similar maritime lithographs after Stopford. We could quickly see that our object lacked the tell-tale grain pattern of the lithographic stone. Besides, lithographs are generally done in black and our object had distinct sepia and bistre tones.

Having ruled out lithography, we found an exhibition catalogue featuring the original watercolour by Stopford, now part of the Cork Port Authority’s collection. The similarity to our object was striking; the smallest details and imperfections seen on the original were also visible on our object. Even the signature was reproduced identically in the bottom right-hand corner. This fantastic detail meant that our image was not flipped, as happens in printing. The discovery compelled us to think that the image was reproduced by a photographic process. We also learnt that the original was in fact of Cobh harbour and was painted in 1852; so the information written on the verso of our object was somewhat doubtful.

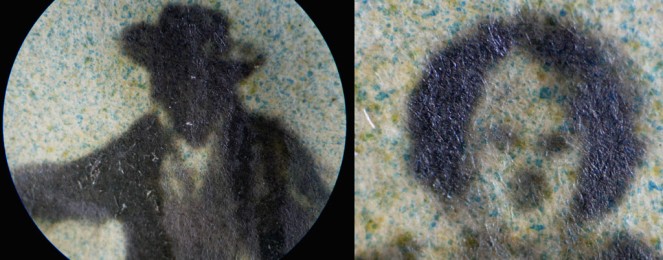

The 1850s were a fundamental decade in the history of image trafficking. For the first time, art publishers had at their disposal numerous ways of reproducing an artwork. But which photographic process had been used to create this image? It was back to the microscope to understand what process was used to reproduce this image. The fuzzy aspect of the edges of the figures continued to confound us. Under magnification, the contours seemed to have been “burned” onto the paper, as if they had been subjected to light exposure. We also noticed a demarcation at the corners of the image, a distinctive element of photographic images. In addition, the sepia and bistre tones are typical colours of early photographic processes and depending on the process used, it was easy to find traces of gelatine or gum on the image surface.

With the help of the Graphics Atlas database – http://www.graphicsatlas.org – and Care and Identification of 19th century Photographic Prints, we compared the date and the documented magnified images of the different processes. We found several possible matches; gelatine POPs was soon ruled out as it was extensively used for commercial portraiture, fine aquatint grain was considered, but our image lacked the smooth gradation of tone this process normally gives. The salt paper process (with gum arabic highlights) gives a similar effect to our ghostly figures but the paper used in that case is generally matte and our paper is glossy.

Lastly, the gum bichromate process, a contact print process based on the light sensitivity of dichromate salts, was considered. Known as the pictorialists’ favourite process from 1885 to 1915, it’s capable of rendering painterly images from photographic negatives – which explains why we have the image in the “positive” sense, with the signature on the right. This gum bichromate process permitted the creator to use painters and photograph’s tools: brushes, pigments and negatives, to directly intervene and give a personal interpretation of the reproduced image. Furthermore, a coated paper that can withstand repeated soakings was used, and this is the type of paper that we have on our object.

Until the 1960’s, most photographs were the result of an impression by contact, which means the negative was the exact dimensions of the original. The gum bichromate process generally has at least two steps. Firstly, glass or paper with a light sensitive emulsion, the same dimensions to the original, and the original are “sandwiched” together. The sandwich is exposed to ultraviolet light such as mercury vapour lamp, a common fluorescent blacklight or quite simply, under the sun. By exposure, the emulsion hardens and becomes insoluble creating a reversed or negative copy of the original on the paper or glass. Then a new blank sheet of paper is prepared with gum arabic mixed with pigment of choice and bichromate. The negative is then sandwiched between a sheet of glass and the prepared paper, and everything is exposed to light again. This creates a positive image on the coated paper. Therefore the paper used for the printing, the ghostly image, clearly seen under magnification, and the surprising dimensions match the gum bichromate process.

In our object, the foreground is produced in this way, but the background is clearly painted in watercolour. Why then did our artist decided to add watercolour to the photographic print? There are two possibilities. Maybe our artist hid the parts he did not want to print on the negative, in order to give free rein to his creative talents. Or, maybe the rendering of the printing of the foreground was not satisfactory and he decided to complete the image with watercolour. The final artist step seems to be the addition of a highlighter, such as glycerine, gelatine or more gum arabic, onto the figures in the foreground, to darken tones and create more contrast.

It remains to be understood by whom, when and why this image was created. We cannot know if the image is contemporary to the drawing or if it was created after. We can wonder if Robert Lowe Stopford or a family member was responsible, seeing as access to the original watercolour or at least its negative was essential to the creation of our object. It’s also plausible that an anonymous artist created this object as a “kitchen-sink” experiment in the early 20th century as he liked the subject!

With thanks: Clodagh Neligan ACR, Senior Paper Conservator, Glucksman Conservation Department, Trinity College Library and Gillian O’Leary, Port of Cork Company - http://www.portofcork.ie/index.cfm/page/maritimeart

The post of Conservation Intern is jointly funded by the National Library and the Heritage Council.