by Katy Milligan, NLI habitué and PhD student at TRIARC (The Irish Art Research Centre, TCD)

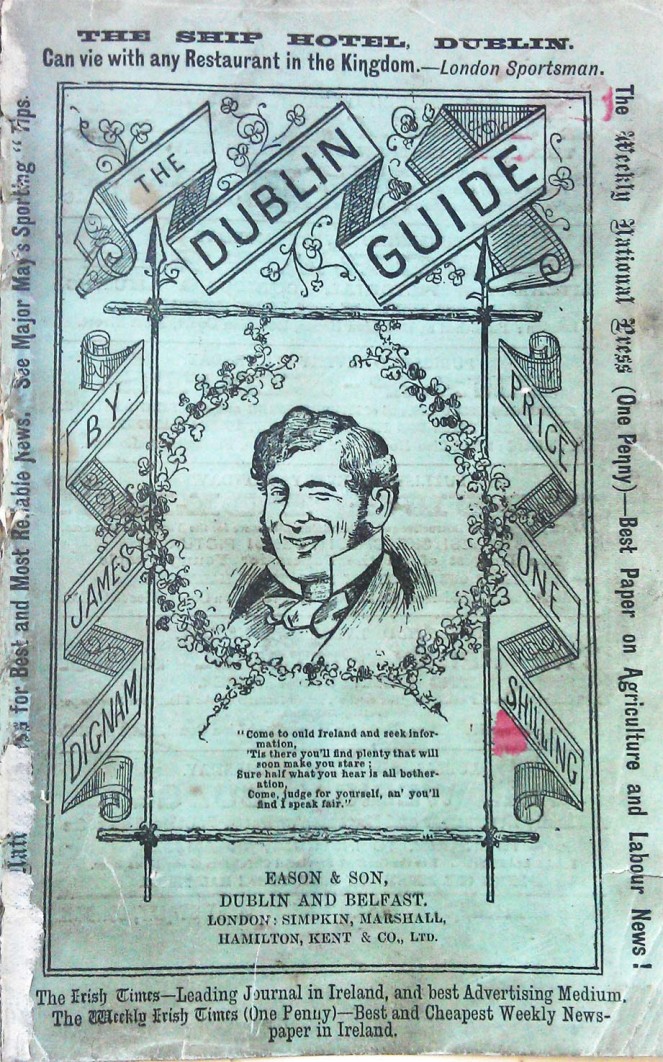

Cover of Dignam's Dublin Guide, 1891 urging visitors to "Come to ould Ireland and seed information, 'Tis there you'll find plenty that will soon make you stare; Sure half what you hear is all botheration, Come, judge for yourself, an' you'll find I speak fair." NLI ref. Ir 914133 d 2

Lurking among the shelves of the NLI is a group of texts which has lately caught my attention. While I intially began looking at guidebooks to Dublin to supplement my current PhD research (which looks at depictions of Dublin by visual artists), I quickly realised that there was another story to be found within their pages. Beyond their interesting illustrations and photographs, the text of these books reflects the changing political situation at the turn of the century, recording the transition of Dublin from a city of Empire to the capital city of an independent Free State. Here, I would like to take two guidebooks, written from differing nineteenth century perspectives, and look at what these guidebooks can show us about Dublin, and the evolving political landscape at this time.

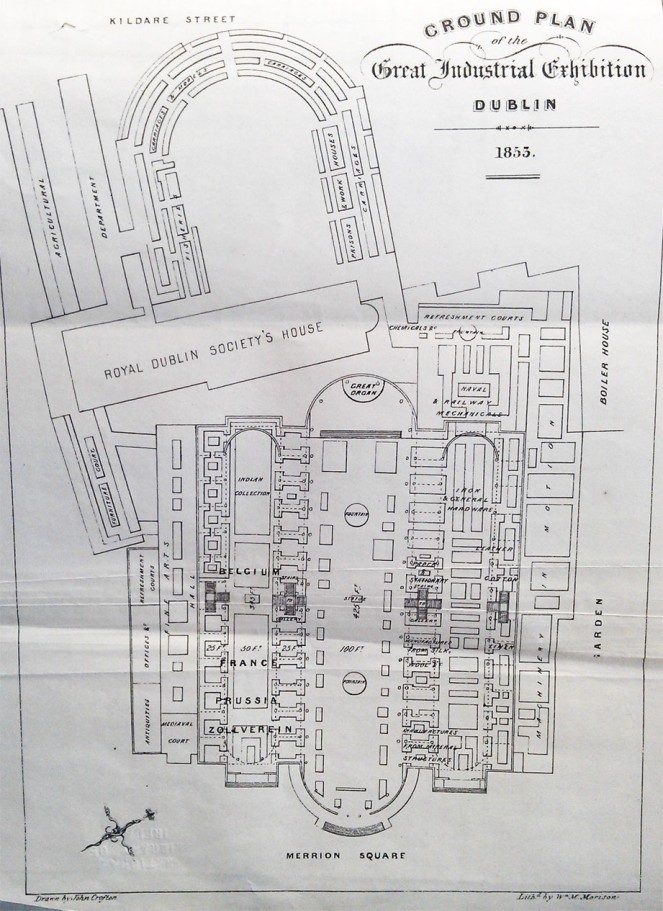

Gound Plan of the Great Industrial Exhibition, Dublin, 1853 from Fraser's Hand Book for Dublin and its Environs. NLI ref. Ir 914133 f 1

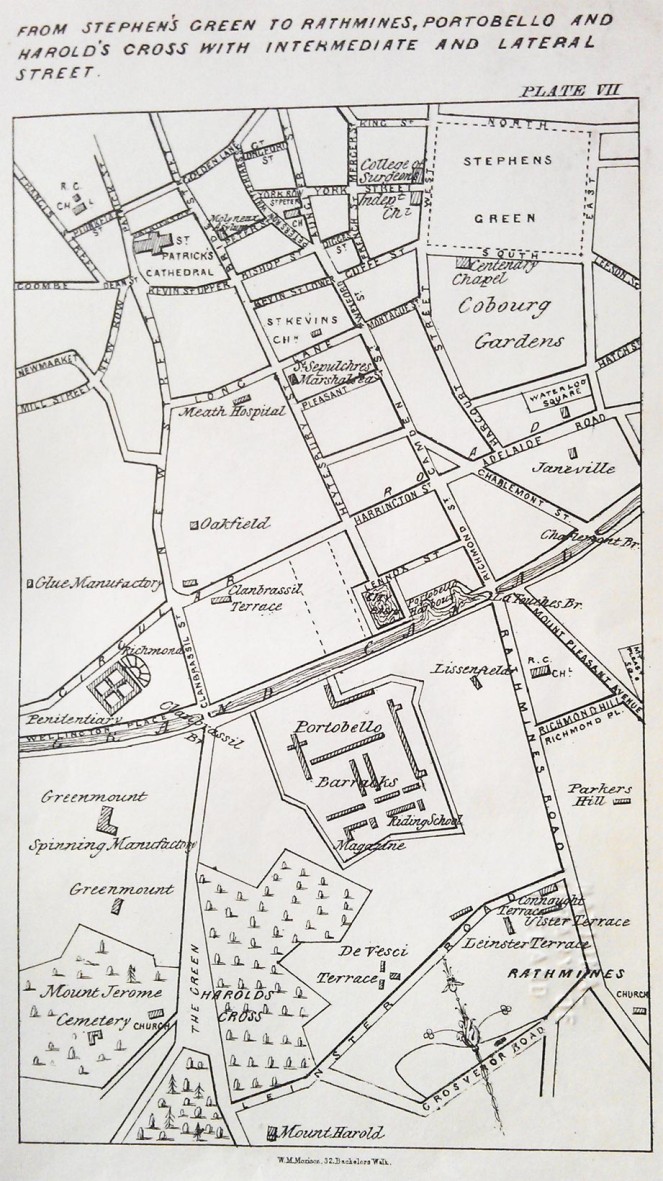

In 1853, guidebooks were produced to appeal directly to visitors to the Irish Industrial Exhibition. Incorporating maps and advertisements for producers at the Exhibition, these texts positioned Dublin within a new, emerging Ireland in the immediate post-Famine period while also remaining conscious of its place within the British Empire. In his Hand Book for Dublin and its Environs (published in Dublin, 1853), James Fraser gave Dublin both a critical and favourable review. He wrote that Dublin, ‘from the comparative paucity of its steeples, towers and domes ... does not form a very striking object from any approach’, but its ‘ample streets, and spacious squares: its magnificent public buildings’ do ‘contribute, not only to make ample amends for its deficiencies in general ... but entitle it to rank as the second city in the empire.’ (Fraser, 20)

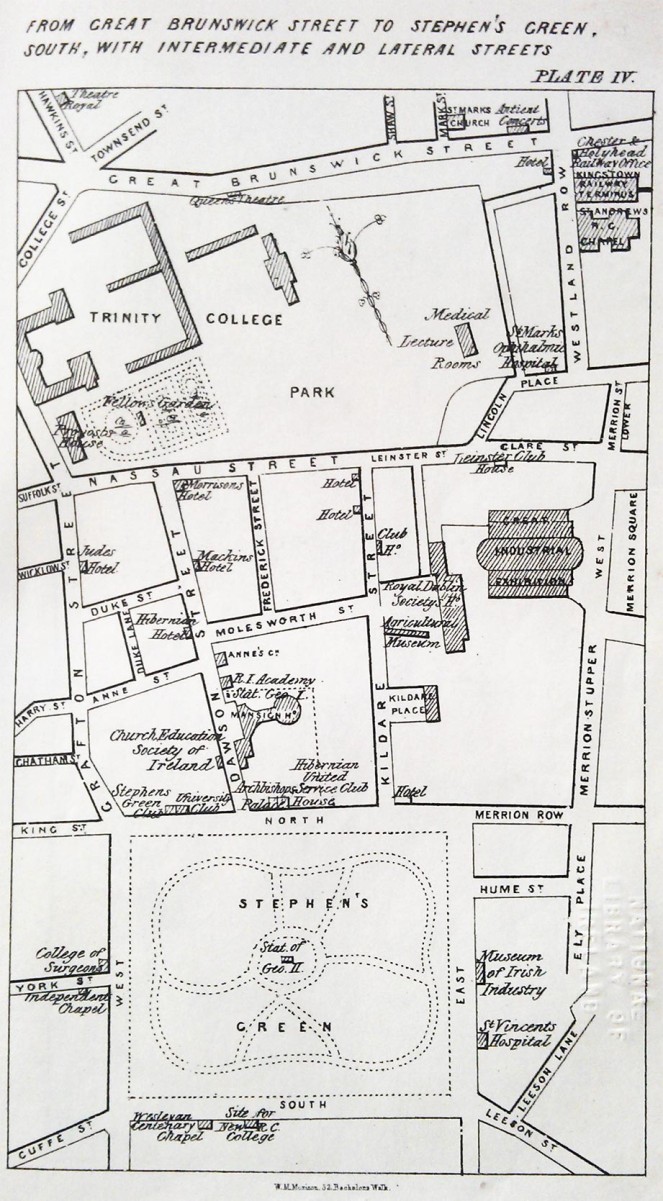

From Great Brunswick Street to Stephen's Green, South, with intermediate and lateral streets, from Fraser's Hand Book for Dublin and its Environs, 1853. NLI ref. Gound Plan of the Great Industrial Exhibition, Dublin, 1853 from Fraser's Hand Book for Dublin and its Environs. NLI ref. Ir 914133 f 1

Fraser acknowledges the effect of the Act of Union on the city, stating that it is ‘no longer the resort of the nobility and gentry’. Despite this, he praises the ‘citizens ... connected with the adminstration of Government and the law ... medical and other learned professions’ and those who ‘encourage every scheme calculated to foster and forward literature, science and art.’ (Fraser, 21) He often uses London as a comparator, noting that ‘the houses in these squares [Merrion, Fitzwilliam] are inferior, in point of style and elegance to those in London’, and that while ‘the best internal view of the city is ... from Carlisle Bridge’, it cannot be for a moment compared with the grandeur of the Thames, and the noble bridges which span that river’. Despite this, Fraser does find some equality between the two cities, finding that ‘the four Railway Termini ... [are] fully equal to any in Britain.’ (Fraser, 21, 59, 40)

From Stephen's Green to Rathmines, Portobello and Harold's Cross from Fraser's Hand Book for Dublin and its Environs, 1853. NLI ref. Ir 914133 f 1

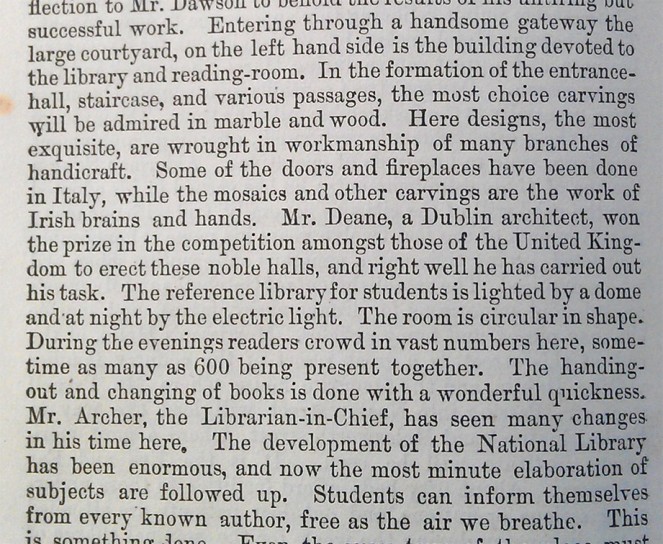

In comparison with Fraser’s guide, Dignam’s Dublin Guide, published in 1891, strikes a markedly different tone. From the beginning, the author makes clear that the guide is intended for ‘those on the far side of St. George’s Channel’. (Fraser, 1) What is interesting about this text is the way it presents a change in the relationship between Ireland and the the United Kingdom; outlining its hopes that ‘we all may forget the mistakes of a cruel past in the warm friendship of a prosperous future ... making our homes in reality of a United Kingdom, under just and equal laws, administered without coercion or fraud’. Later in the guide, the author continues on this theme stating, ‘Henry Grattan’s life and character will always be a bright page in history; and when that freedom he so heroically fought for in 1782 is now almost in our grasp ... Will Home Rule bring this to us at last?’ (Dignam's, 1, 13)

A rave review for the National Library of Ireland in Dignam's Dublin Guide, 1891. NLI ref. Ir 914133 d 2

The growth of Irish nationalism is reflected not only in the author’s references to Home Rule, but also to the cityscape itself. Carlisle Bridge has become O’Connell Bridge, and reference is made to the momentum to re-name Sackville Street, or ‘as some wish to call it, O’Connell Street’, as ‘the majestic statue of the "Liberator of the People" is before us’. (Dignam's, 54) While Fraser had praised Nelson's Pillar as the ‘tribute of gratitude to the memory of our greatest naval hero’ (Fraser, 45), the author of Dignam’s Guide questions ‘Why the pillar was erected in such a place, or in Dublin at all’, responding that ‘it was put here in the past to please our masters, as a mighty record of the greater country, and a quicker mode to Englify us.’ (Dignam's, 62-63) The author of this guide is not blind to the flaws of the city, for example its poor sanitation and widespread poverty, but it is also interesting to note the repeated references to the arrival of ‘provincials’ in Dublin where, ‘the sweet Munster accent of Cork, Tralee or Limerick, is now as familiar in our centre as the voice of the Dublin jackeen’. Just as the monuments and streets of the city take on a more Irish identity, so too do the voices of the people who live and work there. (Dignam's, 7, 3)

Back cover of Dignam's Dublin Guide, 1891, advertising the very chippy and racy Illustrated Bits, "Written by MEN for MEN". NLI ref. Ir 914133 d 2

These are just two examples of Dublin guidebooks from the nineteenth century in the collections of the National Library of Ireland, and there are many more where they came from. With renewed interest in the city and its place in Irish society, these texts make for particularly interesting reading – reminding us that cities continually evolve and change, reflecting the social and political landscapes around them.