by Abigail Rieley - Writer, Journalist, Court Reporter & NLI Reader

The ghosts of the forgotten haunt the National Library of Ireland; those whose stories lie in out of print pages or hidden in the close-knit column inches of microfilmed newspapers. These are the stories lost in the past, forgotten by the public who once pored over every detail at breakfast or during their daily commute to work. These are the stories of murders that were not the cause célèbre of their day, crimes fuelled by greed, or passion, or madness which faded with the newsprint that recorded them, superseded by the next gory interlude, fated to become “tomorrow's chip papers”.

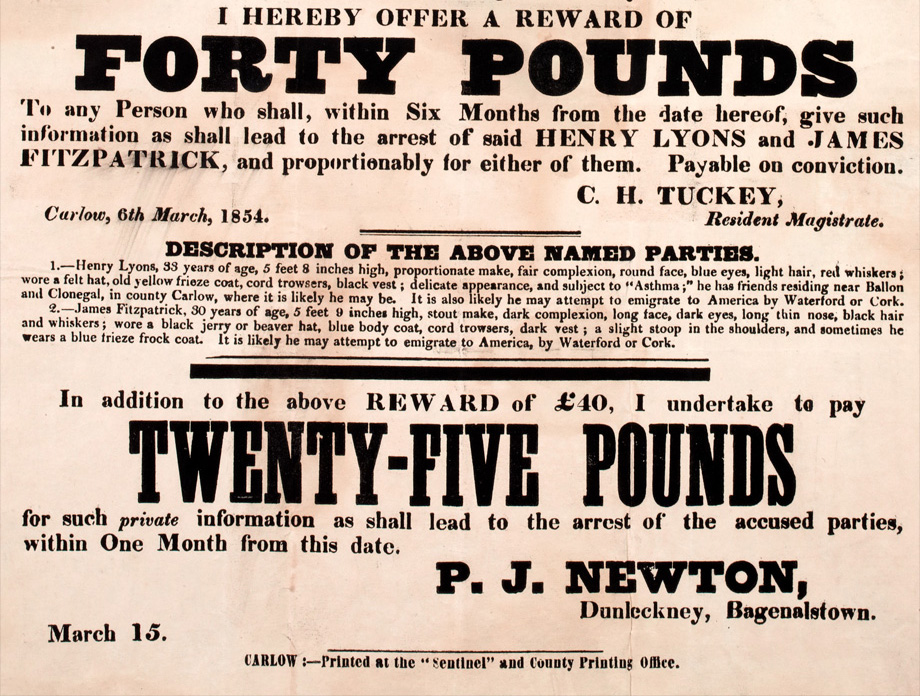

Gorgeously Gory Ghastly Murder Image supplied by photographer Michael Stamp

Murders have always sold newspapers and inspired writers. There's always been a public appetite for misadventure, tragedy and gruesome ends – whether fact or fiction. If “all drama is conflict”, as the old phrase says, then surely murder is drama in its purest form. But we're always on the search for the next big thing so the spotlight quickly passes by. The trials I cover in the shining new Criminal Courts of Justice aren't so very different from the cases that were written about by journalists 50 years ago, or 100 or even 150 years ago.

In his 1946 essay “The Decline of the English Murder”, George Orwell outlined that “perfect murder”, the kind of crime that would still make the headlines. The murderer, he says should be “a little man of the professional class – a dentist or a solicitor, say – living an intensely respectable life somewhere in the suburbs, preferably in a semi-detached house, which will allow the neighbours to hear suspicious sounds through the walls.” He should be a pillar of the moral establishment, Orwell suggested, brought to his knees by a clandestine passion. The crime should be planned meticulously except for the one small detail that allows for his capture, and the release of the story.

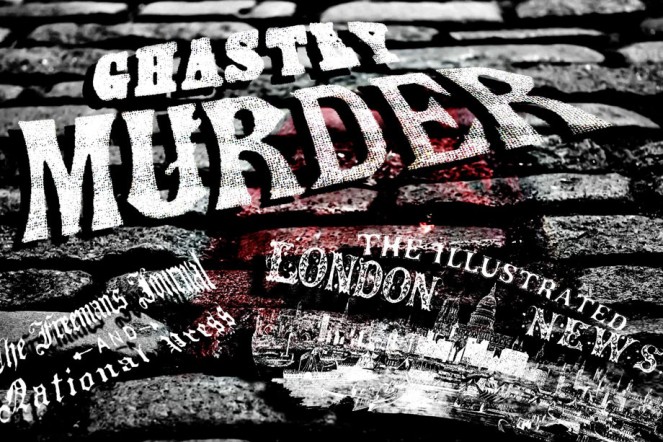

Murder Scene on a Village Road by Charles Cole, 1880 from our Prints & Drawings Collection (PD 2196 TX 56)

Not much has changed, but even by the time Orwell wrote his essay nothing much had changed for more than 100 years of enthusiastic crime reporting. In the 1850s, at the beginning of the 75 year period Orwell named the “golden age” of English murder, the Freeman's Journal, along with most other Irish titles was full of stories about the latest celebrated murder. They drew on stories carried by the London press but also reported home-grown tragedies. Murder might have been a rarer occurrence than it is now but life was brutal and frequently short in those dark days at the end of the Famine. The Freeman's Journal recounted stories of madness, greed and suicide as they appeared in the coroner's court. Many were tragic, many included the promise of a bright new life in the United States. Some were picked up across the British press but all have now been forgotten to be rediscovered in the National Library's record.

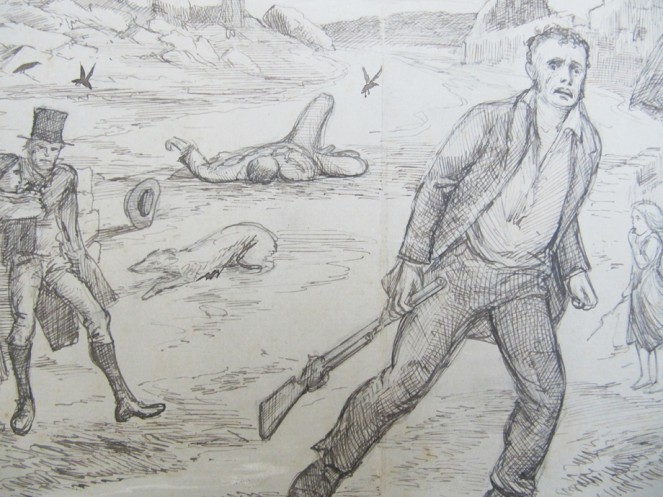

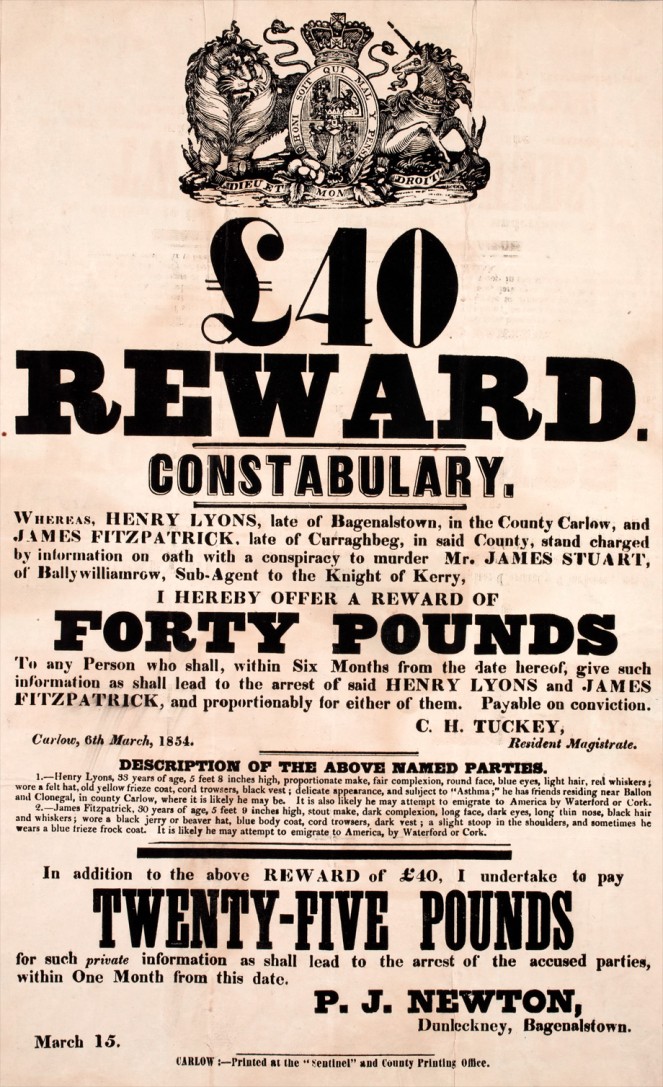

Carlow, March 1854, Reward Poster for two miscreants wanted for Conspiracy to Murder (from our Ephemera Collection)

There was Dr Creighton who, in 1850, slashed the throat of a young female relative before taking his own life. The doctor's family had encouraged him to leave behind his Dublin practice when he had started to become paranoid, “his manner weakened and warped”. He went to live with his elderly aunt, back in Ballinagh in Co. Cavan. One morning he asked his aunt for his cut-throat razor to shave himself – the family had been keeping him away from all sharp implements. A short while later his aunt, hearing noises, went to investigate. She found her niece, Miss Faris, who had been visiting before setting sail to America, lying in a pool of blood in the kitchen. Her throat had been cut. Dr Creighton was in another room, also dead. He was 30 years old.

Or there was Mr Prendergast, whose dismembered body bobbed to the surface of a river in Claremorris, Galway in 1854, to be discovered by a small boy. Prendergast had recently returned from America and had been flashing his money about locally. It wasn't long before suspicion fell on his cousin, also Prendergast, who had tried to stow aboard a ship to the States in a large trunk, his pockets full of his cousin's gold. The nameless but attractive young woman who had hidden him on the promise of a new life in America was distraught when police told her that her boyfriend's wealth was actually that of his mutilated cousin.

Or the mysterious “Daniel H. Webster” who arrived at the door of a brothel in French Street, Dublin on a rainy night in 1853. He claimed to be a veterinary surgeon in the service of Queen Victoria herself, who was visiting the country at the time. Over the next few days he made himself at home, forming an attachment to a particular girl called Emma Fawcett, originally from England. He seemed to have a large number of gold coins in a large trunk he had brought with him. He lavished gifts on Emma and the other girls, but was drinking heavily and frequently morose. One night he took a shotgun and shot Emma and then himself. Emma, luckily, was only injured, but the melancholy Mr Webster was dead, from a point blank blast that left his shirt collar in flames.

Cork, 1931 - Crowd scenes at a murder trial in Cork, illustrating the public appetite for such cases. Suspect inset bottom right (from our Independent Newspapers Collection)

Or poor tragic Mrs Cosgrave, the constable's wife in Loughrea in Galway, who killed her two infant boys in 1852. She was “a person of a morbid and brooding disposition, much prone to novel reading” whose action though brutal, did not bring much condemnation as the papers noted her “secluded life” for much of the past year and her “most affectionate conduct” with her husband.

These are just a tiny fraction of the stories that rest in the National Library of Ireland's collections. The haunting, dark tales that linger in local consciousness and resonate even today. They would be completely forgotten if they weren't kept safely here.

Get Chilled and Thrilled at Library Late, 10 November and 15 December

Bean an Phoist would like to thank Abigail for this post. Really pleased that she could take the time to write it given her own research, writing, court reporting activities (and that's when she's not here with us trawling through our old newspaper collections). And Abigail's is not the only murderous activity going on here at Library Towers this Autumn/Winter. Thursday 20th sees the start of our Library Late Chillers & Thrillers series. That first event's booked out, but you can still book for 10 November (with Gene Kerrigan) and 15 December (with Alex Barclay, Arlene Hunt & Declan Burke).