by Janelle Winters, Manuscript Intern

While sifting through an old card catalogue as part of a grand scheme to augment our online sources, I stumbled onto some 19th century maps of rabies and typhoid fever cases in Ireland. As a former infectious disease and burgeoning history of medicine graduate student, I was intrigued by these unexpected finds. My inner sleuth decided to investigate what other types of public health documents are lurking within the collections of the National Library, an institution not traditionally on the radar of medical historians.

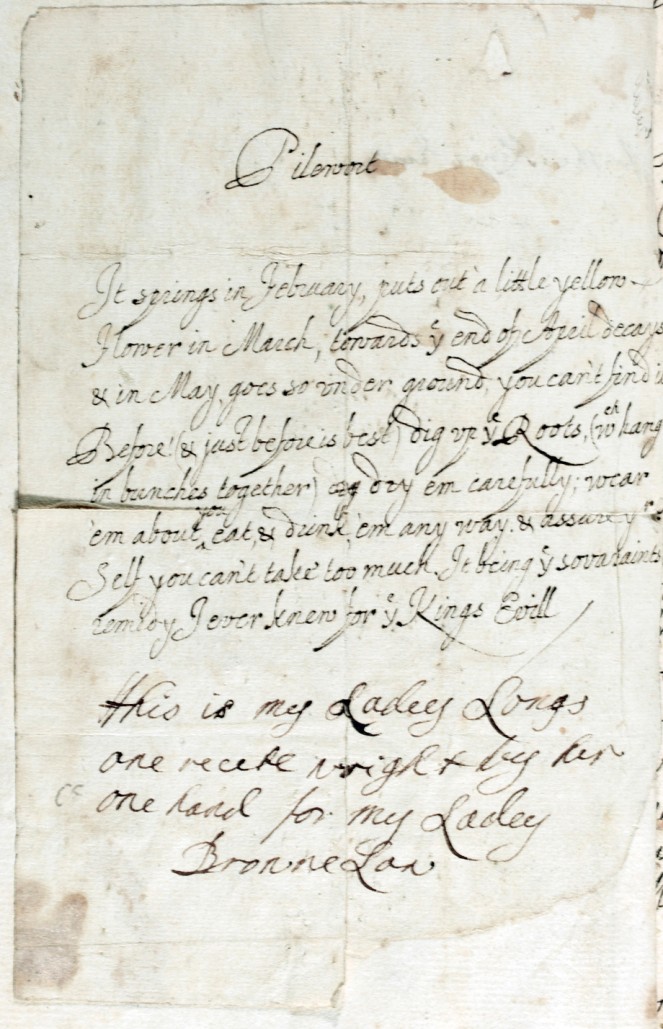

Instructions for use of Pilewort flower, the best "remedy I ever knew for ye Kings Evill", Lady Frances Keightley, Inchiquin Papers, Ms 14786

Before long, I became immersed in the dozens of medical receipt books housed in the Manuscript Department. Within the frayed pages of these books, which largely date to the Early Modern period (16th century to early 1800s), are instructions and testimonials for nearly every malady imaginable (plus receipts for some quite appetizing food). Among the most memorable were a 16th century Latin chant to break evil eye; a 19th century cure for long-term deafness (that involved finding the oldest gravesite in a churchyard, gathering and stamping a yarrow plant from this grave, and dropping its essence into the ear); and 17th to 19th century concoctions for curing sick people bitten by mad dogs, animals bitten by mad dogs, and even mad dogs themselves.

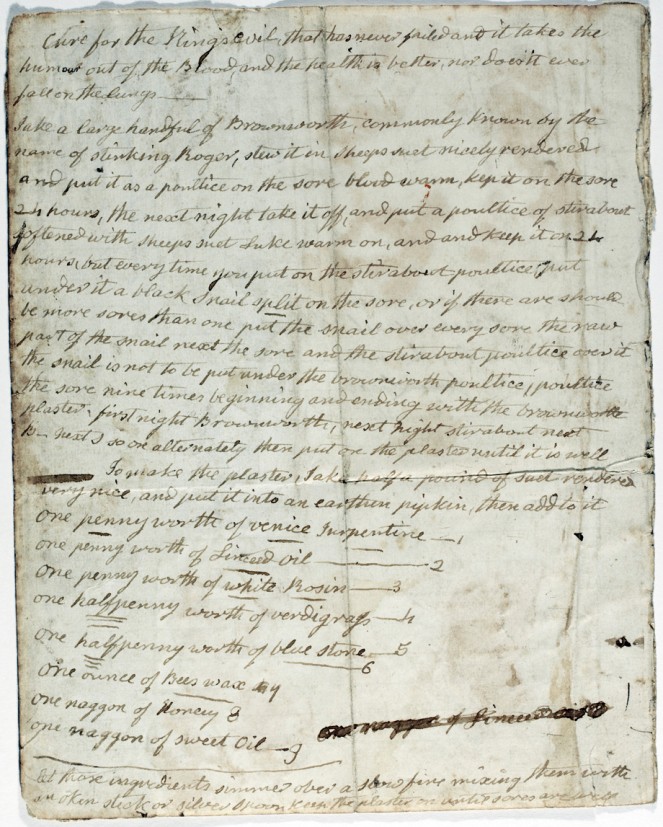

"Cure for the Kings evil that has never failed and it takes the humour out of the Blood and the health is better", Jane Locke, Ms 8353

Perhaps most interestingly, I kept coming across receipts for a condition known as The King’s Evil. Considering that many of these receipt books were compiled by Irish Catholics during a period of British rule, a large proportion of them women, I was curious to know more about this King’s disease and how it fit into Irish history.

A perusal of secondary literature and the Science Museum (UK) revealed that The King’s Evil is a common name for scrofula, or tubercular swellings of the neck lymph nodes. The name referred to the belief that some kings, possibly through a divine right to rule, had miraculous curative abilities for this ailment. Not surprisingly, the Catholic and later Anglican churches often tried to challenge this extension of royal power. Most historians agree that kings going back to at least Edward I (1272-1307) of England and Louis IX (1226-70) of France were reported to cure scrofula by their touch.

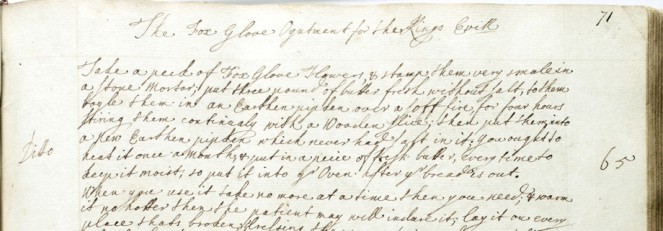

"Take a peck of Fox Glove Flowers and stamp them very smale in a stone Mortar", Lady Frances Keightley, Inchiquin Papers, Ms 14,786, page 71

Thus, during the middle ages and early modern period - until the 18th century in England and 19th century in France - sufferers of The King’s Evil could be either ceremoniously touched by kings, given specially blessed coins or medallions as cures, or treated with various medicines. Historians have not, to my knowledge, described conceptions of The King’s Evil in Ireland, but it appears that a common understanding of this malady entered Ireland with the Norman invaders and English throne.

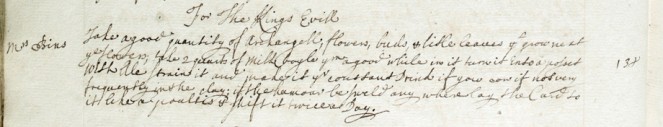

"Take a good quantity of Archangell, flowers, buds", Lady Frances Keightley, Inchiquin Papers, Ms 14786, page 32

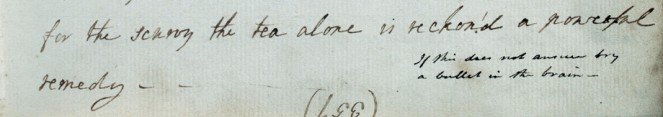

The ‘cures’ written in the Irish receipt books are fascinating. In her compilation of remedies started in 1660, for instance, Lady Frances Keightley (of Dromoland, Co. Clare) has at least three different sets of instructions for curing The King’s Evil. One is the detailed ‘Fox Glove Oyntment,’ which consisted of ‘anointing about the soar as farr as is hard with the Oyle,’ made from boiled fox glove flowers and unsalted butter, and then drinking a complex concoction of herbs. Others describe the merits of ‘Archangell’ and Pilewort flowers. In the mid-19th century, Mrs Jane Lock (of Newcastle, Co. Limerick) and Mary Ponsonby provide intricate recipes for 'plaisters', made from ingredients as diverse as stirabout, ‘stinking Roger', sheep’s suet, black snails, and ‘Cellendine’ leaves. Ponsonby concludes with the wisdom that the recipe also works for scurvy, and either she or another hand has added ‘if this does not answer try a bullet in the brain.’

"If this does not answer try a bullet in the brain" - an amendment to Mary Ponsonby's mid-19th century remedy For The Kings Evil, Ms 5606

These receipts are based on an Imperial naming of scrofula, but they also include uniquely Irish elements, such as using the traditional porridge stirabout as a plaster for sores. While interesting in their own right, they may also be tools for scholars interested in deciphering the nuanced incorporation of English ideas in Ireland. In all, the medical receipt books housed here in the National Library of Ireland offer glimpses into the history of disease, and reveal that medical philosophy often transcended the boundaries of the Church, crown, physician, household, and gender in Ireland.